|

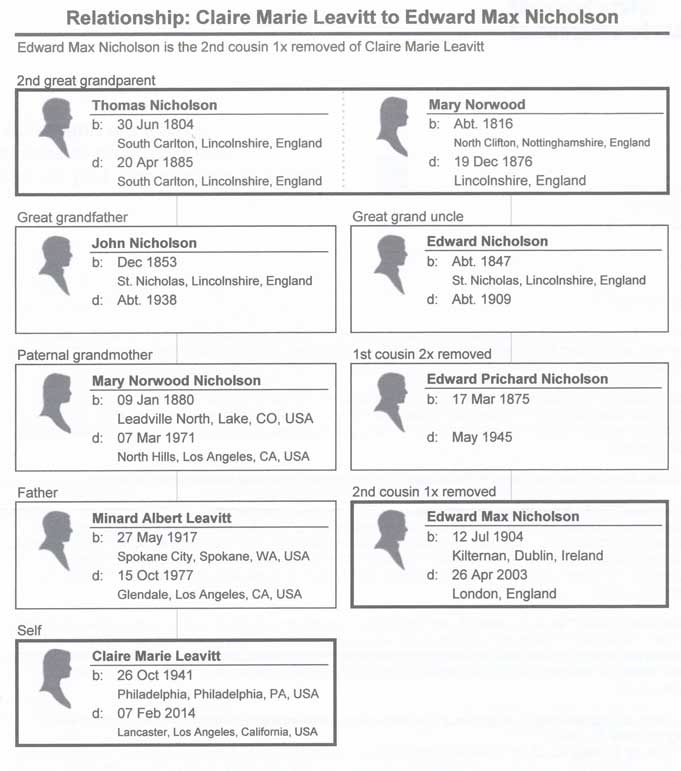

Edward Max Nicholson and my late ex-wife Claire “Clae” Leavitt Sandin were

second cousins once removed. Our children JR and Stuart are

second cousins twice removed and JR’s children are second cousins thrice

removed. Here is more information about Max’s life.

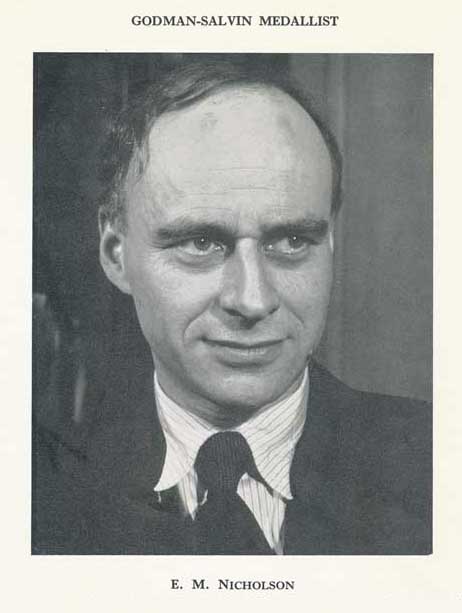

Edward Max Nicholson 1904-2003

Edward Max Nicholson, ornithologist and environmentalist: born Kilternan, Co

Dublin 12 July 1904; Head of Allocation of Tonnage Division, Ministry of War

Transport 1942-45; Secretary, Office of Lord President of the Council 1945-52;

CB 1948; Director-General, Nature Conservancy 1952-66; chairman, Land Use

Consultants 1966-89; CVO 1971; President, RSPB 1980-85; Chairman, New

Renaissance Group 1996-98, President 1998-2003; married 1932 Mary Crawford (two

sons; marriage dissolved 1964), 1965 Marie Mauerhofer (died 2002; one son); died

London 26 April 2003.

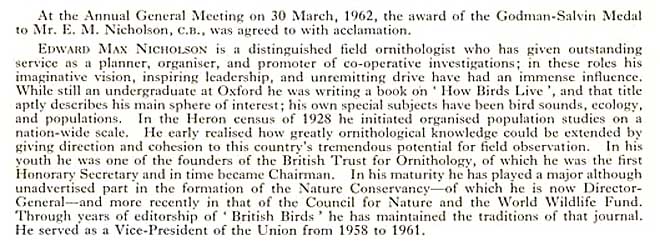

Max Nicholson was a distinguished ornithologist who was

instrumental in the foundation of the World Wildlife Fund (now the Worldwide

Fund for Nature) and the Nature Conservancy (in England, now English Nature), as

first Director-General of which he served from 1952 to 1966. He was also an

environmentalist, with a sweeping vision for the development of London, a

leading figure in the 1951 Festival of Britain, and the founder of the (Silver)

Jubilee Walkway, which now extends over 14 miles through the centre of the

capital.

Sometimes he operated within government organisations, sometimes from outside.

Indeed he saw himself as a scourge of the "Establishment", fervently believing

that Britain could again be a great nation if run by what he called a

"Counter-Establishment". He caused more than a small stir with his 1967 book

The System.

Although he appeared on such radio programmes as Desert Island Discs,

and was active until the end with the New Renaissance Group, Nicholson was never

a household name and, despite the attempts of others to secure honours for him,

most recently in the magazine Country Life in January, he was relatively

un-honoured. He never sought personal glory and tended to be dismissive of those

who had. Instead he sought to get things done, and he was one of those people

that, once you have heard their name, crop up everywhere: he seemed,

mysteriously, to be the mastermind of an enormous number of well-known and

successful enterprises. Having read his unpublished memoirs, I am convinced that

he was an OM manqué.

Edward Max Nicholson came from generations of stolid Lincolnshire farmers. His

father, Edward Prichard Nicholson, was a professional photographer in Dublin,

and his mother, Constance Oldmeadow, was the daughter of the Chief Clerk and

Chief Superintendent of the Cheshire Constabulary. Max was born in 1904 at

Kilternan, south of Dublin, then part of the United Kingdom. The family returned

to England when Max was five, after which his father scraped a living as a

portrait photographer near Staines.

As a young boy, following a visit to the Natural History Museum, and further

inspired by Gilbert White's Natural History of Selborne, he formed a

lifelong interest in bird-watching, and began keeping a list of birds seen,

beginning with the treecreeper, great tit and blackheaded gull in 1913. This

exercise became so extensive that he and Sir Alan Brooke would compare

ornithological notes when attending the Cairo Conference during the Second World

War.

He won an exhibition to Sedbergh (and, when his father failed to complete paying

his school fees, repaid them later himself). After school he spent his time

seeking out and writing about birds – he was proud to claim that by the age of

21 he was one of the few men alive making a living out of birds. He undertook

journalism, produced guidebooks and presently tackled leaders for Geoffrey

Dawson, Editor of The Times. On Dawson's advice, he went up to Hertford

College, Oxford, in 1926, rather later then was usual, with a scholarship to

read History.

At Oxford he founded the Exploration Club, and took part in expeditions to

Greenland in 1928, and to the Amazonian rain forest in British Guiana in 1929.

His interest in birds led him to organise the 1927 Oxford Bird Census and, in

1928, a national census of heronries. In 1932 he was a founder of the British

Trust for Ornithology and its first honorary secretary.

His career as an ornithologist gave him particular pleasure. He found that a

close study of birds gave him rare insight into the ways of men. He relished the

speed with which birds took decisions, and he enjoyed the kind of photographic

memory that enabled him to take a walk in the woods, and then recall the birds

that he had seen with sharp accuracy hours later.

He put his knowledge to good use. There were a variety of books, Birds in

England (1926), How Birds Live (1927), The Study of Birds

(1929), The Art of Bird-watching (1931), and two books of wild-bird songs

in collaboration with Ludwig Koch in the mid-Thirties. Later he produced

Birds and Men (1951), Britain's Nature Reserves (1957) and, as

recently as 1995, Bird-watching in London.

He was Chairman of the British Trust for Ornithology between 1947 and 1949 and

was involved with Peter Scott in founding the Severn Wildfowl Trust. He

initiated and was first chairman and chief editor of the great nine-volume

Oxford series The Birds of the Western Palearctic between 1965 and 1992.

From 1980 to 1985 he was President of the Royal Society for the Protection of

Birds.

In between this overriding interest Nicholson spent many years in public

service. In 1930, he became an assistant editor on the Weekend Review,

drafting in 1931 "A National Plan for Britain", on the basis of which the

socio-economic research organisation Political and Economic Planning (PEP) was

founded; he was its secretary until 1940, and its chairman after the war. He

served on a small team with the Ministry of Information drafting national

messages for the outbreak of war, but resigned in disgust in October 1939.

Meanwhile he also served on an unofficial Post-War Aims Group that advised the

Foreign Secretary, Viscount Halifax, who sent Nicholson and David Astor to Paris

to report on French attitudes in December 1939.

In March 1940 he was head-hunted by Lord Hurcomb and Sir Arthur Salter to the

Ministry of Shipping, serving first as head of their Economic and Inter-Allied

Branch, and then as Head of the Allocation of Tonnage Division (liaising with

Washington) between 1942 and 1945, which involved him in numerous transatlantic

crossings during the Battle of the Atlantic. In his capacity as senior adviser

on the availability of cargo shipping, he attended the conferences at Quebec,

Cairo, Yalta and Potsdam.

Needless to say, he never trusted the Civil Service. He avoided political

parties, despite loving politics, and literary circles, despite being a lifelong

admirer of good English.

Between 1945 and 1952 he was head of the office of the Lord President of the

Council, Herbert Morrison. He accompanied Morrison on critical trips to

Washington, and went to Berlin with him to help boost morale during the historic

airlift of 1949. He took part in Sir Henry Tizard's new advisory council on

Scientific Policy and initiated the Festival of Britain, guiding it through

numerous crises. (Years later Terence Conran told him that as a young man of 20

he had visited the festival, was impressed by the designs, but surprised that no

one was selling them. He decided to have a go.)

In all Nicholson spent six years at the centre of post-war reconstruction, only

returning to the world of birds in 1952, when he became Director-General of the

Nature Conservancy, which he had helped to set up, in his 14 years at the helm

establishing nature reserves and protecting by law Sites of Special Scientific

Interest (SSSIs).

A key achievement was to chair the initial organising committee for the World

Wildlife Fund in 1961. With his friend Aubrey Buxton, he was instrumental in

directing the Duke of Edinburgh towards conservation. The Duke's involvement

with the World Wildlife Fund enabled him to travel the world, virtually as a

head of state, allowing him to make valuable contributions without apparently

straying into the fray of politics, since, as Nicholson enjoyed pointing out,

the politicians of the early 1960s had little conception of environmental

issues.

Other environmental schemes with which he was involved were the International

Institute for Environment and Development (of which he was a founder council

member), the UK Programme Committee for World Conservation Strategy (as Chairman

from 1981 to 1983) and Earthwatch Europe (as first Chairman, 1985-90). Between

1963 and 1972 he was Convenor for the International Council of Scientific Unions

of the conservation section of its International Biological Programme. In more

recent years he founded Land Use Consultants in 1966, serving as chairman. His

last scheme was the New Renaissance Group, which shaped projects for an

over-arching professional College of the Environment, served as an international

training centre for a bio-diversity survey, a Council of Culture and other

bodies with which Nicholson had been closely involved for over 40 years.

More books dealt with these interests, the most notable being The System,

subtitled "The Misgovernment of Modern Britain" and followed by The

Environmental Revolution (1970), The Big Change (1973) and The New

Environmental Age (1987). Sadly no publisher seemed inclined to publish the

autobiography on which he had been working for many years.

With his experience of the Festival of Britain in 1951, and its attendant

problems, Nicholson was not surprised when the Callaghan government showed no

particular interest in celebrating the Queen's first 25 years on the throne in

1977. It took Charles Wintour, then Editor of the London Evening Standard,

and Illtyd Harrington, Deputy Leader of the Greater London Council, to promote

this celebration with a clarion call to the nation on the front page of the

Evening Standard in August 1975.

Far from being in good time for 1977, Nicholson worried that they were too late

to make an impact. However, he saw the Silver Jubilee as an opportunity to lift

the celebrations into "the realm of inspiration and guidance for the future,

which after all was the basis of the Festival of Britain's lasting influence and

prestige".

He developed a document called "The Seven Thrusts" in which he declared he was

not content to leave "a haphazard legacy of scattered unrelated Jubilee halls,

gardens, fountains, seats and suchlike" but intended to initiate an overall plan

for ongoing projects in partnership with local authorities and voluntary bodies.

The first of these was the (Silver) Jubilee Walkway, which aimed to knit London

more closely together, and in particular to lure the walker from Leicester

Square across Lambeth Bridge and on to the South Bank. He wanted the walker to

pass by areas of the city noted for entertainment, assembly, ceremonial,

open-air activities and national history. Nicholson hinted that perhaps this

walker would be subtly changed by what he or she absorbed from "this fertile

heritage". The walkway proved one of the most durable of the environmental

memorials to the Silver Jubilee and has flourished to this day.

His second thrust was to knit north London together by the fuller use of

Regent's Canal and the Grand Union Canal: he was pleased that by opening the

towpath it would be possible to walk 20 miles from the Colne Valley to the Lea

Valley along a car-free route. The other thrusts involved the cleaning up and

development of the Covent Garden area, improvement schemes overseen by the Civic

Trust to develop a London-wide heritage and amenity programme, an extensive

tree-planting programme and the development of "meanwhile" use of derelict land,

which included the creation of an urban farm at Newham. He also masterminded the

Clean Up London Campaign.

I remember sitting with Max Nicholson one afternoon in Hyde Park during one of

the sporting activities of the Silver Jubilee Celebrations. He spelt out his

plans for London and, as with so many men of vision, he made it all sound so

simple. He spoke of how the Thames should again become a working feature of

London life, of his plans for the canals in north London. It was at an unveiling

in connection with the Jubilee Walkway that I met him again some 22 years after

that first conversation. He was as alert as ever in his 97th year.

He told me that he liked to divide his attention into an equal study of the

past, the present and the future. He was against the Establishment, though a

dedicated monarchist, and predicted that the monarchy would survive the 21st

century, since any sensible person would realise that the system was patently

more honourable than a presidency of ambitious and self-serving politicians. He

said that he believed that we had lived through the American century, but that

the two major powers in 50 years' time would be Britain and Russia.

His philosophy as a nonagenarian, he said, was a dialogue between his brain and

his body. He was a believer of mind over matter, but conceded, "I occasionally

give up something as a result of what my body tells me." He drove a car with a

clean licence for over 70 years and, though he had travelled the world from pole

to pole, was contented to spend most of his time in London, in Chelsea, in the

home he had bought some 60 years before.

Nicholson described himself as "impatient, irascible and hyper-critical", often

condemnatory of others, yet he was often seen as a conciliator, a healer of

dissension and a champion of tolerance. When he accepted the Gold Medal for the

World Wildlife Fund from the Duke of Edinburgh in June 1982, he described

himself as a man who had been dreaming for the best part of 78 years.

"Imagination is the stuff that dreams are made of," he said:

"Without it we become prisoners of the built-in stationary bias of our

institutions and our education, with fatal results for society and our own

mental well-being. We miss the essential challenge."

Max Nicholson's voice was one that should have been heard

more widely, but we live in an age when the media are more interested in

scoundrels than men of achievement. He was sanguine about this. "To me the gift

of continuous perception is all the heaven I want," he said.

Hugo Vickers

AFTERWORD

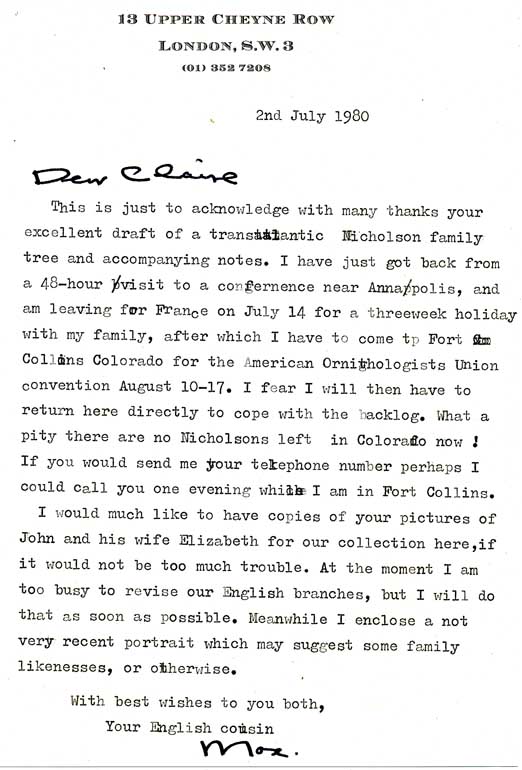

Clae and I met with Max in Santa Monica, California in about 1968 when he

was on a US tour. He and Clae exchanged family information after that

meeting.

As you can see, they were second cousins once removed, making JR and

Stuart second cousins twice removed and JR’s children second cousins thrice

removed. Max was the Ornithologist (Birdman) of the family!

Stuart Sandin and cousin Max Nicholson would have had a lively discussion

about birds. In the mid-90s Stuart worked with endangered birds on the Big

Island, including the ‘akepa, Hawaii creeper, and the 'akiapola'au, banding

birds and catching the birds’ invasive predators.

Then on Maui, Stuart worked with the Maui Critically Endangered Forest

Bird Project through the National Biological Service (now USGS Biological

Resources Division). This project focused on the po'ouli, trying to find

the last remaining individuals (they found three, and now they are all gone).

|

|

|

|

|

|

|